– If the reports from that time are true, you unexpectedly made the national team in the fall of 1961, and then you mysteriously disappeared before you could play. What happened to you between October 18 and 25?

– I'll tell you in a moment, but if brought them with you, I'd like to look at the articles first.

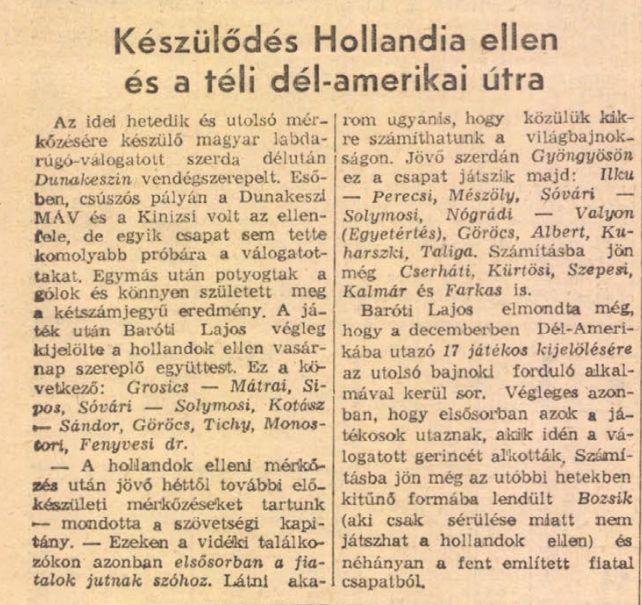

– Here they are, look! Ilku – Perecsi, Mészöly, Sóvári – Solymosi, Nógrádi – Vallejo, Göröcs, Albert, Kuharszki, Taliga. According to Népszabadság, this was the starting eleven announced on October 18, 1961, by Lajos Baróti, the head coach who wanted to try out some young talent for the Hungarian national team's match against Gyöngyös in preparation for the World Cup in Chile. A week later, the team won 9-0, but the minutes show that Vallejo's name was not in the record books. Instead, János Farkas, who made his debut in an official national team match two months later, was in your place.

– The events date back to early September. At that time, I was a right winger for the NB II team, VM Egyetértés, and we played a training match with the national team at our Soroksár field in early fall. Everything worked out for me; even when I was accidentally hit with the ball, it still bounced in the right place. I scored a goal, I assisted once, but we lost 3-2. Lajos Baróti liked my performance and wanted to put me on the national team.

– What stopped you?

– The fact that I was a Spanish citizen. At the time, dual citizenship was not allowed, and I had to decide whether to give up my Spanish nationality for the Hungarian national team.

– The World Cup in Chile was approaching: a dream opportunity for a twenty-year-old second-division footballer.

– Yet I said no. I was brought up at home that we can't change our nationality like we change our shirts. I considered myself Spanish, and I still feel like that wholeheartedly, it's part of my identity. Even though I could not reconcile myself to the Franco regime and I do not agree with the current government either.

– How did you end up in Hungary?

– I would like to start from earlier. My parents and my brother, who was less than a year old, fled to France in 1939 to escape the Spanish Civil War. My father had previously taught communications at the military academy in Madrid, he was a high-ranking officer, and after the defeat of the war, he as a republican, couldn't stay there. He could expect reprisal and could have been executed. I was born in France on July 3, 1941, in a small settlement called Saint-Julia. Shortly afterwards, we moved to the village of Juzet-d'Izaut where we lived until 1948, after which we moved to Toulouse. My father could no longer accompany us there.

– What happened to him?

– During the war, he kept a telegraph, which the French authorities found on him during a house search. At the time, there was great fear in France of Spanish weapons, especially Basque explosives, and my father insisted that he had kept the device to teach his sons how to use it, but they didn't believe him. Yet even my brother and I were called in, and, to prove his testimony, we were perfectly capable of operating the device at the age of five and eight. In the end, the French deported my father to Corsica where he was made to do forced labor. Afterwards, he never spoke of his ups and downs. Religion was also a taboo subject at home, although it later emerged that he was originally destined to be a priest; he spent two and a half years in seminary as a young man. After he died, I was surprised to see the cross around his neck.

– The family has still not arrived in Hungary...

– In Moscow, the Spanish Communist Party reached an agreement with Stalin and the French government that Spanish refugees in France would be accepted by the socialist countries. My father wanted to go to Czechoslovakia, but the Czechoslovak quota had been filled by then, so we were allocated to Hungary. He was transported by a Polish boat from Corsica to Gdansk, and my mother, brother and I traveled by train for three and a half days, until all four of us finally arrived in Budapest in November 1951. The Hungarian Workers' Party gave us an apartment at 12 Váci út where I lived until my marriage in 1965. One hundred and twenty Spanish families had arrived in Hungary at that time, and we had a joint club where we met regularly to talk and dance.

– How did you cope with the Hungarian language?

– My brother and I spoke French well, so we were enrolled in a Hungarian private class with a native French speaker, but I got bored after two lessons and went to play football on the dirt field at Béke Square instead of attending the lessons. When our parents asked the teacher about us, she told them that the older child was diligent, but she never saw the younger one. I suspect, by the way, that I learned the beauties of the Hungarian language on the football field before my brother learned it from the French teacher. First, of course, the obscenities. I remember that in the first few weeks, I was abused by my peers for not knowing the language. When I wanted a glass of water, the boys would always help me with the request. They made sure I went up to the school teacher and told her nicely and politely to “fuck off.” Of course, I took the advice, and the teacher just looked at me with her eyes wide open. Then, seeing all the children giggling in the background, she realized we had been the victims of a dirty joke.

– How did the Béke Square footballer almost become a World Cup player for the Hungarian national team?

– I started playing football at the Angyalföld Sports School, and after I had aged out of the youth team, I was approached by the Kőbánya Brewery team. They offered me three hundred liters of beer a month if I signed for them, but I didn't like beer very much, so I signed for second division club Egyetértés. There I played with footballers like Imre Ombódi, Sándor Oborzil, and Ferenc Somodi.

– What did Egyetértés offer to say no to three hundred liters of beer?

– The caterers' association offered me a retail operation contract, the same reward the other players got. But I had no desire to run my own pub. Instead, I took a job as assistant manager of the Berlin Restaurant where I met many people from the football world, including Lajos Tichy, the striker for Honvéd who used to come here with his wife. My career as a caterer was helped a lot by the fact that the catering director of District V watched our match against the Hungarian national team, and for some reason, he wanted to make me a manager afterwards, and sent me to the Mátyás Cellar for an internship. Then an opportunity came up in the foreign trade line, I became a salesman for Nikex and Komplex, a job I held until we moved to Spain in 1972. My football career was over by then, a cruciate ligament rupture suffered at Egyetértés put a stop to becoming more, although I did play briefly for Gázművek at the invitation of coach Ferenc Kunos.

– Why did you return to your parents' country?

– I joined Hungarotex's partner company in Spain where the favorable tax rules in the Canary Islands made it easy to trade in textiles, sheets, towels, and curtains. At the same time, I worked for other Hungarian companies, Tungsram, Artex, Metalimpex, Metrimpex, and Elektroimpex. I was doing well until 2001 when the Chinese invaded the market, and it was impossible to compete with them: they offered their products at half price. Traveling there was not easy as in the early 1970s, my wife waited almost a year for her passport. In the end, the way we traveled with our two children to visit relatives in Spain, was that we, parents, did not eat anything during the three-day trip because we had a total of twenty dollars.

– Didn't the Hungarian secret service try to take advantage of your extensive international contacts and your embeddedness in Spain?

– Nothing like that has come up. They didn't try to recruit me, but even if they had, I wouldn't have done it. But I know someone who was approached and said no, and he's paid the price.

– Based on articles published in the 80s, you were privy to the inner circles of Spanish football. You introduced Népsport's correspondent to Helenio Herrera, you sent László Dajka to Las Palmas, and you were on the bench alongside Ferenc Kovács for the 1986-1987 season.

– At that time, an interpreter was even allowed to sit next to the coach. Ferenc Kovács was a great coach, but he needed help with communication. I first translated for him when he was still giving an interview to a Spanish radio station from Budapest. Then, when he arrived, we became friends quickly through the medium of Imre Csillag, a journalist from Barcelona, and from then on, I accompanied him as much as my job allowed it.

– Did Ferenc Puskás's return home in the 80s make the news there?

– He was very much loved in Spain, even after he moved back home. I met him twice: once at a Honvéd match where Lajos Détári was playing, and again in 1995, at the Régi Sipos restaurant where the Golden Team players were arguing about whether the player or UEFA would win the Bosman case. Ferenc Puskás was sure that UEFA would win, but to the surprise of many, I started arguing with him.

– Was there a political message in the Franco regime that it welcomed Ferenc Puskás who had sought a place in Western Europe after 1956?

– Franco, as an enemy of communism and a supporter of Real Madrid, embraced the Hungarian footballer with a good heart. What this meant for the player, I do not know. Puskás was a common man, and he never politicized.

Translated by Vanda Orosz.