Melbourne is the Trianon of Hungarian sports

Hungary remembers the day of the outbreak of the 1956 Revolution. The events from 65 years ago radically defined the history of Hungary and, of course, its sports life. October 23rd is a national holiday in the country, as is March 15, but in connection with the illustrious date, October 6 shouldn't be forgotten either, which is the day of the execution of the Martyrs of Arad, or June 16, the day of Imre Nagy and his associates' execution.

Today, when we live in a free world, it is strange to remember the times when the struggle for freedom was the condition for a better life. During the Revolution, the Hungarian athletes decided to draw attention to the events in Hungary with their results at the Melbourne Olympics (November 22 to December 8). Their appearances – 9 gold, 10 silver, and 7 bronze medals – prove this and speak for themselves. Hungary won 16 gold medals in Helsinki and many experts predicted that the Hungarian national anthem would be played more times in Melbourne, but instead, traveling there was already problematic...

The man on the street was fighting for the revolution, while the athletes representing the homeland was fighting for gold 20,000 kilometers away. Let's put it pathetically: they were patriots, even though the team was not homogeneous in terms of their political view. There were left-wing thinking people, people to whom the Rákosi era gave opportunity to study and play sports, and there were those, who, under their family or social embeddedness, were not, to put it mildly, adherents of the existing regime at that time. And yet they wanted the same thing: the "Russians" to go home, and Hungary to be independent. When the Hungarian athletes flew to the Games from Prague (they founded a revolutionary committee in Nymburk, near the Czechoslovak capital while waiting to leave) with chartered planes, the country was already occupied by Soviet troops. The competitors left their families and homes in that environment. They were accompanied with wild news along the way, and during the Olympics, they were kept in fear and terror by even more terrible news. Let us note that the importance of the crushed revolution is proven by nothing more than the fact that Spain, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, which were in solidarity with the Hungarian nation, already ordered their athletes home from Australia, and the Dutch boarded the plane that took them back home on the day of the opening ceremony.

The Hungarian athletes' thoughts were about their country; they were watching the domestic news. The Australian press reported on handcuffing young Hungarians to transfer them to the Soviet Union – which even Hungarians, emigrating to the fifth continent after World War II, did not refute... No wonder, if subconsciously only, the question of good or bad performance has become secondary for them. Not one of them spent nights wondering whether to say goodbye to Hungary forever or return to uncertainty. Is it any wonder that the tensions in the Hungarian-Soviet water polo match were in such a state of mind, where one of the opponents, Valentin Prokopov, punched Ervin Zádor? The image of his bleeding face traveled all over the world like mementos: well, the Soviets are violent even in sports. Although the Russian water polo player knew what was happening in Hungary but he had nothing to do with politics, it would have been difficult to explain this to outraged viewers and readers of international newspapers.

The Hungarian gymnast girls won their gold medals on the last day, December 7, and if the athletes had been sleeping anxiously because of the concern for their relatives, they then had to think of their future. At the closing ceremony, for the first time in the history of the Olympics, the participants did not march with their own team but mingled among themselves. IOC President Avery Brundage reportedly granted the form-breaking farewell by fulfilling a Chinese boy's request. The following text appeared on the scoreboard: "The City of the Olympics says goodbye to you and wishes you a safe trip!" Many Hungarians wondered where was the safe trip to: should they return home, or choose freedom thousands of kilometers away from home?

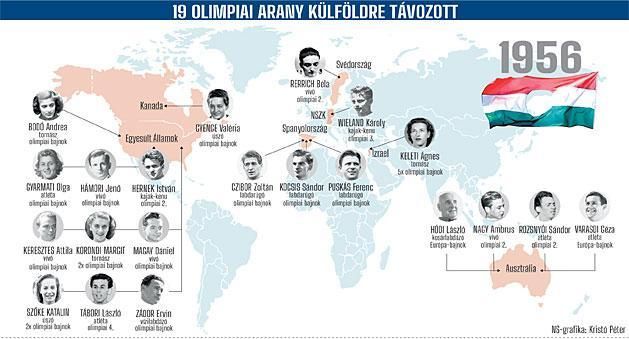

Although the Hungarian national football team did not participate in the Olympics, the footballers' lives – to name only the three most famous ones, Ferenc Puskás (whose fake death was reported during the Revolution), Sándor Kocsis and Zoltán Czibor – were also affected by the revolution and emigration or even by the return home. Sport, revolution, Olympics, emigration. If we ask ourselves how the revolution, the Olympics and emigration have affected Hungarian sports as a whole, it is clear that no positive answer can be given. Olympic champion gymnast Erzsébet Köteles gave the most inspiring, yet heartbreaking answer: "Melbourne is the Trianon of Hungarian sports." While the decision taken in the castle near Paris mutilated the territory and population of the country, with the period after 1956, 40 of the 113 accredited competitors became immigrant Hungarians.

According to the proverb, when one door closes, another opens. U.S. Vice President Richard Nixon, in solidarity, has not put a barrier to accepting Hungarian refugees. Alexander Brody, who never forgets his Hungarian roots and has an interest in sports, organized an American trip, named Hungarian Freedom Tour, thanks to Sports Illustrated's support. The athletes who did not return to Hungary arrived in San Francisco on December 23. Brody says those who had used the events as a kind of indicator to shape their own lives made the right decision. A few months later, water polo players László Jeney and György Kárpáti, fencers József Sákovics and Lídia Dömölky returned home in 1957, but the rest settled into the society there. How did they relate to the old country? Dániel Magay, Olympic champion in team fencing said: "There are two types of people: some can completely assimilate and never want to return to Hungary again, and some consider themselves Hungarian and would always go back. I think I'm somewhere in between: I'm not giving up on being Hungarian, but from here, I can see things from a different perspective than if I had stayed." However, they are no different in that almost all of them have enhanced the reputation of Hungarians.

When Hungarians put the symbol of revolution, the badge depicting the Hungarian flag with a hole, on the lapel collar of their coat on October 23, they shall not only remember the revolution that erupted 65 years ago but their Olympians in Melbourne as well.

Translated by Vanda Orosz

Curtis pofonvágta az őt gyalázó szurkolót a lelátón

Az MU egyszer találta el a kaput, de egy szerencsés góllal így is nyert

Ez nem hiányzott: Szoboszlai Dominik még egy világsztár miatt aggódhat!

Milliárdokért árulja luxusotthonát az olimpiai bajnok

Villámgyors finomság – az 5 legjobb tejbegrízrecept

Orbán Viktor elutazik, ezen a helyen magyar kormányfő még nem járt

A szlovénokat legyőző Horvátország lesz a mieink negyeddöntős ellenfele kedden 18 órakor a kézi-vb-n

Szoboszlai szenzációs passzán ámul a világ - videó

A Chiefs újabb drámai meccsen nyert a Bills ellen – triplázás kapujában a Kansas City!

Chema Rodríguez: Óriási dolog, hogy sorozatban harmadszor ott vagyunk a nyolc között

Hétfői sportműsor: olasz, spanyol és angol futball, magyar futsal